This year’s Jaipur Literature Festival featured luminaries from the literary, academic, and scientific worlds and offered audiences conversations and debates on subjects ranging from cancer survival, rape, and racism to climate change, genetics, artificial intelligence, and the psychological aftermath of migration.

Women and power, the adaptation of books into screenplays, America’s secret wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and mapping the heavens were just some of the other topics discussed during the five-day literary extravaganza, held in Jaipur’s Diggi Palace.

Lighting the candles to open the festival.

The Jaipur event, which is the largest free literary festival in the world and now attracts about 500,000 visitors, was this year attended by more than 500 speakers hailing from more than 35 different countries.

The youngest writer presented this year was ten years old. Eighty-one percent of those attending the Jaipur literature festivals are under the age of thirty.

This year’s keynote address was given by molecular biologist Venkatraman (Venki) Ramakrishnan, who talked about the role of science in today’s world.

Ramakrishnan has a breadth of knowledge that is mind-boggling, but he speaks with modesty. He was joint winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2009 for his work uncovering the structure of the ribosome and has just written his first book for the general reader, Gene Machine.

He told the audience at Jaipur that he was trying to immunise himself against “Nobelitis”: Nobel laureates starting to believe in their own genius.

“Being here today gives me an opportunity to talk across the divide between the humanities and sciences that has plagued many societies for a very long time,” he said.

“All of us should enjoy science and mathematics, which are as much a triumph of human achievement and as much a part of our culture as history, literature, art and music.”

It was objective scientific and technical knowledge, Ramakrishnan said, that created wealth in the past and still does today. “Today, countries that are resource poor but knowledge rich do very well. Switzerland and Singapore are classic examples.”

It was objective scientific and technical knowledge, Ramakrishnan said, that created wealth in the past and still does today. “Today, countries that are resource poor but knowledge rich do very well. Switzerland and Singapore are classic examples.”

Knowledge has deep consequences for our wellbeing, Ramakrishnan says. “As Feynman once pointed out, there is beauty in both the poet’s and the scientist’s description of a rose.”

Today, Ramakrishnan says, science is more important than ever and Indians should be learning it in their own language. “We live in a world in which science and technology are ubiquitous; decisions are constantly made by governments, corporations, educators and others that affect us in profound ways.

“Can we use energy as we do in the modern world without risking destruction of the environment? Can we feed a growing global population? Should we change a person’s genetic makeup to prevent or cure a disease. How do we keep our privacy in an increasingly digital world?”

Ramakrishnan talked about being an outsider, as an immigrant and being outside the main fast track of science. The latter, he said, may have been an advantage in his work, enabling him to avoid the pack mentality.

He also talked about the tension of having to compete as scientists. The system, with its competitions and having to publish in certain journals to be recognised, exacerbated this, he said.

Opening the festival, Sanjoy Roy spoke about how literature is able to elevate us and transport us into another world. Writers, he says, look into the “crystal glass of the future” and can put in place a vision for all of mankind.

The Nigerian poet and novelist Ben Okri is one such visionary. He is not only an extraordinary writer; he is also a compelling speaker. His answers to questions are poetic in themselves. In explaining his vision of the world, he is thoughtful, insightful, and imaginative.

When Okri won the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1991 for The Famished Road, he was, at 32, the then youngest winner of the prize.

When Okri won the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1991 for The Famished Road, he was, at 32, the then youngest winner of the prize.

“Everything that is great that lives transcends the boundaries of its definition,” Okri told the audience at Jaipur. The act of writing at its highest and purest, he said, was “the closest people come to meditation in this secular world”.

When one woman in the audience said she had no time to read slowly, Okri told her that he would rather she read just one paragraph well than a whole book badly. “It’s precisely because you are busy that you should read slowly,” he said. “One sentence in a good book can change your life.”

Reading slowly, Okri told the audience, “is like entering into someone else’s dream”.

Okri’s new book is entitled The Freedom Artist. A young woman called Amalantis has been arrested for asking the question “Who is the Prisoner?”.

When Amalantis disappears, her lover Karnak goes looking for her. He searches desperately at first, then with a growing realisation that, to find her, he must first understand the meaning of her question.

Okri told the audience at Jaipur: “Freedom doesn’t mean the freedom to burp in someone’s face, to be rude to someone you don’t know, to be inhospitable to strangers in your house.”

Freedom, Okri says, “is the allowing of someone else’s genius to flower so that my genius can flower”.

The whole of literature, Okri told the audience, emerges from the questions human beings ask about reality.

Okri says that, after his first manuscript was accepted for publication, he was practically levitating for six days afterwards. He says that he has never lost that feeling and feels more vulnerable and excited after each book is published.

Fiction ‘sails through time’

Another of the key speakers at Jaipur was the author of Life of Pi, Yann Martel, who also speaks very thoughtfully. His presentation of his ideas is unrushed.

In conversation with author and translator Jerry Pinto, Martel talked about language, mathematics, and writing Life of Pi, which he described as a “past incarnation of my curiosity”.

Pi, religion, and art are all slightly irrational, Martel says, but they all help us make sense of the world.

Martel told the audience how India has inspired him. The country is a vast buffet, he says, and it brought him multiplicity. “I was drying up and India nourished me with its monsoon rains.”

Martel told the audience how India has inspired him. The country is a vast buffet, he says, and it brought him multiplicity. “I was drying up and India nourished me with its monsoon rains.”

In India, everything is there to be seen and selected, and loved or hated, he said. “Whatever gain and pain is right there.”

Martel said he wrote Life of Pi “to try and understand the mechanism of faith”. He said his next book would be about the Trojan War. It will be an “anti-plutocratic discourse”; a dialogue between two voices on the subjects of antiquity and modernity, fiction and non-fiction.

Fiction, Martel says, sails through time and it is best if history is expressed as story.

Martel cited the example of the Holocaust. “Why are we so limitive when we talk about the Holocaust?” he asked. “The big tomes on the Holocaust that are the ones that are go-to texts are all works of non-fiction and when you get fiction it’s very thinly disguised biography or autobiography.” There is a fear of fiction about the Holocaust, Martel says.

Surviving cancer

Martel’s session was followed by one in which the actress and author Manisha Koirala talked to Sanjoy Roy about surviving ovarian cancer. Koirala has now been cancer free since 2015. “There is a life after cancer,” she told the audience, “and it may be a better life than before.”

Koirala talked about going to New York for cancer treatment, which involved an 11-hour operation. She also spoke about the importance of patients being informed, about changing her lifestyle and giving up alcohol, about tackling depression, and about the importance of good emotional health. She talked about introspection and correcting her mistakes.

“Rather than following other people’s ideals and ideas of how you should be living your life, you need to dig deep. You need to find what really makes you happy.

“You need to find your passion, you need to find what is it that will make you tick. Finding that and living that actually is an alignment with your truth.”

Koirala said she followed her doctor’s advice to the tee, but then took responsibility for retrieving her health. We need to take ownership of our own health, she says.

She spoke about the excruciating loneliness and fear she felt when diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

She also told the Jaipur audience about the warning signals her body gave to her and recounts the time, about six months before her diagnosis, when two healers scanned her body and told her that her ovaries were red hot.

By the time she was diagnosed, the cancer was at a very advanced stage and had spread to other organs.

The book Healed, which Koirala co-wrote with Neelam Kumar, begins with the words “I don’t want to die”. When one is diagnosed with cancer, Koirala says, “the first thing that happens to us is the thought of death”.

Talking about facing death, she said; “I feel when it’s our time to go … we should be graceful about dying and death and accepting this well.” However, as long as we were alive and there was a will and a way, we should do our level best to be well again, she said.

Koirala is now training almost every day for a trek to the Everest base camp that she will do with two friends from school.

Koirala is now training almost every day for a trek to the Everest base camp that she will do with two friends from school.

She said that one thing that had helped her evolve during her battle with cancer was understanding that our time on this planet is limited.

“It made me just value what I have. It made me value my life, my time, and my health so I became more grateful for what I have and started paying attention and honouring it more.

“I realised that we are all interconnected. Doing good to others is also doing good to ourselves as well.”

Born into a politically prominent family in Nepal, Koirala is the granddaughter of Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala, the first democratically elected prime minister of the country.

She was appointed as the Goodwill Ambassador for the United Nations Population Fund in 1999 and was involved in relief work after the earthquake in Nepal in April 2015.

Father and daughter

The first session on the main stage was an endearing conversation in which the renowned poet, writer, and director Gulzar and his filmmaker daughter Meghna talked to editor, author, and film buff Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri.

Meghna talked about her father’s “very equal” approach to parenting and his being a friend and confidant, but being stern when necessary. “He always talked to me,” she said. “He never talked down at me, which was very, very precious for me.”

She also talked about the development of her filmmaking career and the difficulties of the first 15 years. The appetite for the kind films she makes, which are based on true stories, is very recent, she says. “It’s the stories I am now telling which are making me the filmmaker that I am,” she told the Jaipur audience.

True life, Maghna says, is possibly the strongest source of stories that we have. “I think they’re far more engaging and far more connected to our society because they’re immediate; that connection is very, very immediate. Your imagination doesn’t come into play to make that connect, which will happen with fiction.”

The next film Maghna will direct will be focused on the life of acid attack survivor Laxmi Agarwal and, Maghna says, will tell the larger story of acid violence in India.

Acid attacks

Even though, in 2013, India’s Supreme Court ordered states and union territories to regulate the sale of acids and other corrosive substances and make acid attack a non-bailable offence, it is still easy to buy acid over the counter.

India still has the highest incidence of acid attacks in the world.

One of the speakers at Jaipur was acid attack survivor Reshma Qureshi. An activist, model, and vlogger, Qureshi fronts the NGO Make Love Not Scars (MLNS), which supports acid attack survivors. In 2016, she went down the catwalk at New York Fashion Week.

She was on stage at Jaipur with the CEO of MLNS, Tania Singh, with whom she wrote Being Reshma, and MLNS founder Ria Sharma, whose own memoir was released at the festival.

Qureshi fronted the #EndAcidSale campaign. Her videos for the campaign garnered more than two million views overnight and 350,000 people signed her petition addressed to India’s prime minister in which she demanded an end to the over-the-counter sale of acid.

Being Reshma not only tells the horrific story of what happened to Qureshi; it recounts other incidents of violence in her family that preceded the attack and is a powerful appeal for social justice.

Being Reshma not only tells the horrific story of what happened to Qureshi; it recounts other incidents of violence in her family that preceded the attack and is a powerful appeal for social justice.

When Qureshi was attacked by her estranged brother-in-law and two other men she was just 17 years old and had dreams of becoming a teacher. She is severely scarred on her face and arms and lost her left eye.

An acid attack, Qureshi writes, is vicious, but what follows is “a toxic barrage of stereotypes, pity, and discrimination”.

She writes that, after the attack, she felt that humanity had ceased to exist.

“My eyes had swollen shut, my face was blistering with boils, and here was a police officer asking why I, the victim, wasn’t answering his questions,” she wrote.

‘Sexualising crimes of violence’

Violence against women was also one of the main topics discussed in the conversation on the first day of the festival between the controversial author, columnist, and academic Germaine Greer and British author Bee Rowlatt. Rowlatt wrote In Search of Mary about Mary Wollstonecraft, who authored the landmark feminist text A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Germaine Greer, whose influential first book, The Female Eunuch, was published in 1969, talked about women not knowing when they are in danger from a man they are with. “We think we want Mr Right, but in fact we are terribly attracted to Mr Wrong,” Greer said.

Talking about rape, Greer said it was “an aspect of our degraded sexual relations and our failure to respect each other”. It doesn’t have to draw blood, she says; “it can be done by the man you love most in the world”.

She insists that the violent element of rape needs to be called by a different name. “When you eviscerate a young woman; when you pull her entrails out with a starting handle, you have to call it a different name.”

When there is such brutality and a woman is killed, “it’s not a rape case; that’s a murder case,” Greer said.

If a penis was all a man had, Greer says, she wouldn’t need to be afraid of him. “I’m more afraid of his thumb, which can pull my eye out. I’m more afraid of his elbow. I’m more afraid of his cruel tongue that can say things to me that stay stuck in my head and really degrade my feelings of worth and honour.

“We keep sexualising crimes of violence. What is important about them is not that they are sexual, it’s that they are violent.”

Greer brought humour into the debate when she remarked that the penis was not her enemy. “In fact it’s the only part of a man I know what to do with,” she remarked.

Greer, who is now 80, also had the audience laughing when she dismissed the book Fifty Shades of Grey as a dreary, badly written “horny-free zone”.

Greer, who is now 80, also had the audience laughing when she dismissed the book Fifty Shades of Grey as a dreary, badly written “horny-free zone”.

Greer also talked about women writers of the past. “What was being sold,” she said, “was the woman herself rather than the work.” The work was mostly very fashionable and commercial, Greer said. The women were chained to their publishers and were forced to “cannibalise themselves”. Very often, she said, the women were housekeepers, bedmates and, by the way, providers of copy.

What is less well-known about Greer is that she is an active environmentalist. She bought sixty hectares of land in Australia’s Numinbah Valley and set up the Cave Creek Rainforest Rehabilitation Scheme. She has written a book entitled White Beech: The Rainforest Years about what was, before white settlement, the most valuable form of timber tree growing in the southeast corner of Queensland.

“Within a generation or two it was logged out; it was gone,” Greer said. “One of the things I have been doing is bringing it back again, learning how to propagate it.”

She says that, at the end of years of hard work, she’s not sure that biodiversity on her land has improved. “I rather think it hasn’t,” she said. There were more insects when she came onto the land in 2001, she said, and the pythons were disappearing.

Women and Power

Greer also took part in a “Women and Power” session with journalist and author Reni Eddo-Lodge, award-winning journalist Namita Bhandare, and classicist Mary Beard, in conversation with Bee Rowlatt.

Mary Beard’s books include Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town, the bestselling SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome and the feminist manifesto Women & Power.

Mary Beard’s books include Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town, the bestselling SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome and the feminist manifesto Women & Power.

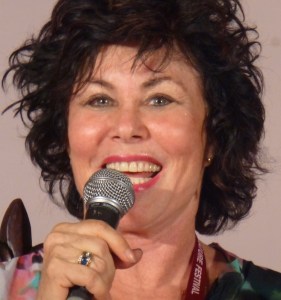

Talking about the Odyssey, Beard (pictured left) cited a moment in the epic poem in which Penelope, the wife of Odysseus, is told by her teenage son Telemachus to shut up; that speech is man’s business.

This, Beard said, was “a foundational moment in the silencing of women”. Beard traced some of those moments through history and “the use of classical myth to disempower women who wanted a public voice and a public position”.

There is a long tradition going back as far as we can see “which actually manages to explain human disaster, warfare, tragedy, and the loss of men by the fault of a single woman”, Beard says.

She says that Helen of Troy, “who happily didn’t exist”, is in a sense one of the origins of the desire to blame the woman for the boys’ “adventures, disasters, violence, and catastrophes”.

Eddo-Lodge (pictured below right) spoke about the #MeToo movement and how it is “women globally reckoning with power”. The movement, she said, continued to inspire her.

“As feminists we exist in this interesting dichotomy; we see where we lack power; we see where the power structure is cutting us out or at least trying to push us onto the sidelines, but also within that we have to reckon with the structural power that we do benefit from.”

“As feminists we exist in this interesting dichotomy; we see where we lack power; we see where the power structure is cutting us out or at least trying to push us onto the sidelines, but also within that we have to reckon with the structural power that we do benefit from.”

Eddo-Lodge pointed to the rich, privileged Hollywood actresses who, she says, kicked the movement into the mainstream. “They were incredibly powerful and still reckoned with rape and sexual assault within their jobs,” she said.

She talked about the power that exists between women – race and class – and how these things get in the way of the solidarity that women could be building.

If we are looking to build broad coalitions in the feminist movement, the huge economic disparity between women is something that has to continue to be addressed, Eddo-Lodge says.

“My personal experience, being involved in feminism since I was a student, was white women in particular wielding racism against me; whenever I spoke up about racism, speaking to me as though I was the problem, seeking to marginalise my voice, and these were women who I thought I was working with.”

When this initially began happening to her, Eddo-Lodge says she felt a huge sense of betrayal.

Eddo-Lodge took part in a session the previous day entitled “Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race”, which is the name of her award-winning book and earlier viral post.

She described racism as a “social construct to organise power in society”.

In the “Women and Power” session Greer talked about the discrimination against older women in the feminist movement. She cites the “much-hated mother-in-law” who has to struggle to carry out her ordained role.

“We still haven’t figured out how we can make our notions of power, which operate at street level, operate at a higher level or at the institutional level,” Greer said.

Beard says that, whether it is in the home, or on the shop floor, or in parliament, “the fact that women are not taken seriously means that we all lose out”.

Bhandare talked about the low percentage of women in the Indian parliament, about agricultural tools in the country being designed by men for men, “but men don’t use them; it’s women who use them”.

Bhandare talked about the low percentage of women in the Indian parliament, about agricultural tools in the country being designed by men for men, “but men don’t use them; it’s women who use them”.

The workplace, Bhandare says, is designed by men. The most educated women, she says, are dropping out of work the fastest. “RIght now, only 24 percent of women are in the labour force,” she said. The Bollywood film industry, she adds, “is a wonderful little brotherhood” designed by men.

Bhandare says we have to look at the #MeToo movement not just in relation to sexual harassment, but in broader terms. “I think the fundamental fight really is for dignity and equality and to win a place around the table.”

‘Political theatre’

MP and author Shashi Tharoor is a regular at the Jaipur festival and spoke at several sessions, including one entitled #Tharoorisms.

MP and author Shashi Tharoor is a regular at the Jaipur festival and spoke at several sessions, including one entitled #Tharoorisms.

He was asked in a press conference about freedom of speech under the Modi government. He said intimidation of journalists had been rife. A lot of it was not as crude as censorship, he said, but was pressure on owners.

Tharoor also spoke about the controversy over the the Sabarimala temple in Kerala where there have been protests over women of childbearing age wanting to enter the temple.

In September last year, the Supreme Court ruled that restricting entry of women of menstruating age was unconstitutional.

However, the Kerala state government faced difficulties executing the court order because of massive protests.

Tharoor said the CPI(M) and BJP parties in Kerala had converted the Sabarimala sacred shrine into a “place of political theatre”, and this he deplored.

Author Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni also says the situation should not be made into a big political issue. It should be women who decide whether they should enter the temple or not, she says.

The Forest of Enchantments

Divakaruni was at Jaipur to launch her new book The Forest of Enchantments, which is a retelling of the epic the Ramayana from the viewpoint of Sita.

She told Changing Times that she is going to write about other strong women in history, but is keeping their names secret for now.

She is currently working on a historical novel about a woman she says was forgotten by history, but was very important. She reveals only that it is an Indian woman who lived during the time of British rule.

“There are only a few lines about her in history, but they’re very evocative lines. From that I’m doing research and creating her story.”

Divakaruni says The Forest of Enchantments will be easier for readers who are unfamiliar with the Indian epics than The Palace of Illusions, which is a retelling of the Mahabharat, because the Ramayan doesn’t have many characters. “There are just a few major players,” Divakaruni said. “It’s a linear story.”

She says that, when she is writing a book based on an epic, she is able to focus on character, nuance, and voice as the plot is already there. “It’s exciting in a different way. When I’m writing a book that’s my own story, I’m creating that world so there’s a real pleasure in that, but when I’m rewriting the epics, then that world is already there, but it’s a wonderful world so it’s a great pleasure to dive into that world and then just focus on the great characters and reinterpret them.”

Divakaruni says the women she focuses on were not fully represented in the epics. “The original epics have them all. I’m not creating any characters, but they’re glossed over because the project of the epic is a different one and it’s not one about women.”

Other writers are now following her lead, she says. “I think there is a movement now, slowly. Other writers are doing this, yes, but I think when I wrote Palace of Illusions, there really wasn’t. So that became a groundbreaking book, which was wonderful but a great surprise to me. I didn’t know it would take off like that.”

Divakaruni says she feels a great need to put a woman in the centre of a story, of a book, of a world. “When I’m rewriting an epic I’m completely immersed and I’m very happy.”

She says she doesn’t miss the kind of storytelling she has done in the past and says she is still telling stories: the moments not brought up in the epics such as the kind of conversation Sita would have had with her mother just before her wedding.

“What kind of advice would she give? The epics don’t talk about those moments, but they’re of great interest to me.”

Divakaruni told the audience at Jaipur that women’s stories are not just about one woman, they are about a whole community of women.

“I think this is in general true of women’s stories. There could be exceptions, but I think this is how women work; cooperatively. We gain our strength from each other. That is our big strength as women and we should not lose that. We should remember that we need to stand up for each other because we need to move forward as a group.”

Listening to each other’s stories as women is very important, Divakaruni says.

‘What we talk about when we talk about rape’

In a session entitled “What we talk about when we talk about rape”, which is the title of her latest book, Sohaila Abdulali talked about being kidnapped, robbed, and raped when visiting India for the summer. Abdulali was born in India, but lives in the United States.

Abdulali was a minor at the time of the attack and, to avoid being locked up herself, she lied and made a statement to police saying nothing had happened.

She talked in Jaipur about how silence perpetuates rape. “If we remain silent, rape will continue because there is no accountability,” she said.

‘When you are depressed you are moving through cement’

The American actress, mental health campaigner, lecturer, and author Ruby Wax also spoke with great honesty, and was extremely funny.

When she arrived on stage she talked about the broken tree bough that injured four other people in a lunch area and fell on her. “I’m a bit frazzled,” she told the audience. (Frazzled is a word she is fond of and uses often.)

When she arrived on stage she talked about the broken tree bough that injured four other people in a lunch area and fell on her. “I’m a bit frazzled,” she told the audience. (Frazzled is a word she is fond of and uses often.)

Wax talked about suffering from depression, which, she says, arrives like a tsunami and is nothing to do with burnout.

“When you are depressed you are moving through cement,” she said.

Talking about the medication she has been on “since the beginning of time”, she says it is only guesswork; “it’s like setting a fire to a whole forest, but one tree is sick”.

Wax spoke about ending up in an institution. Not wanting this to happen to her again, she became interested in psychology. “I read about what had the most positive results and it seemed to be mindfulness and cognitive therapy.”

She went to Oxford, wrote a master’s dissertation, and then a book entitled A Mindfulness Guide for the Frazzled. Her second book is entitled How to be Human and is a three-way encounter between Wax, a monk, and a neuroscientist and was described by the actress Joanna Lumley as a handbook for those in despair. “It is actually for everyone alive, for the curious, or disillusioned or muddled or just plain happy,” Lumley wrote.

Wax talked in Jaipur about people not having time to love themselves. “There is too much choice,” she said “It’s very hard in this culture to wake up in the morning and feel OK.”

She says she has learnt that approximately four out of every five thoughts are negative. “When you are happy,” she told her audience, “try to remember it.”

We know, Wax says, about outer space, but very few people know about inner space. We are now stressed about stress, she says, and the 21st-century disease is that we are distracted.

Wax’s definition of happiness is being able to pay attention when you want to, and not getting dragged into something else. “I missed my kids’ childhoods because I was on the telephone,” she said.

Wax talks about people needing their tribe. She has organised “Frazzled Cafés” in numerous cities in Britain in partnership with Marks & Spencer. People sign up online and then meet every two weeks in groups of about 15 with a facilitator.

The Frazzled Cafés, Wax says, are not just for the one in four people who suffer from diagnosed mental illness at some point in their lives. “It is for the four in four feeling frazzled and overwhelmed by the stresses of modern life.”

In Britain and the US, Wax says, people are dispersed and competing with each other. “We’re going to have to upgrade ourselves as much as we upgrade our iPhones.” We need, Wax says, to practice compassion, and that takes courage, “and that’s what it is to be human”.

Where does fiction come from?

The American author Andrew Sean Greer, whose novel Less won the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, took part in several sessions, including one with Ben Okri, Tania James, and Vikram Chandra, in conversation with Chandrahas Choudhury on the subject “Where Does Fiction Come From?”

The American author Andrew Sean Greer, whose novel Less won the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, took part in several sessions, including one with Ben Okri, Tania James, and Vikram Chandra, in conversation with Chandrahas Choudhury on the subject “Where Does Fiction Come From?”

Greer, who wrote his first book at the age of 16, says he wanted to write fiction quite simply because he was a big reader.

He said he loved it when he had an idea that was clearly too big for him because then he knew that he wouldn’t run out of steam.

Less is the story of Arthur Less, a floundering author on the brink of turning fifty, who receives a wedding invitation from his ex-boyfriend. Instead of facing his heartache and confronting his feelings, Arthur packs a bag and heads off to literary events around the world.

Greer compares writing Less to going on a couple of dates with someone and not knowing how long it will last, then signing up for a two-month cruise with them in a cabin without a window.

Okri talked about the short story being a “monk’s discipline”, self denial akin to cutting out carbs and sugar. The writer has to be very rigid and rigorous, he says.

The novel, Okri says, is a very generous and forgiving form. “You can waffle in a novel for three hundred pages and still have a great novel, but the short story betrays itself in every sentence. The novel is more responsive to spontaneous inspiration.”

The poetic must be kept alive, Okri says, “and the precise must be kept clean and functional”.

Freedom of the imagination

The issue of freedom was also highlighted by the author Irvine Welsh, who wrote the cult novel Trainspotting.

Welsh remains passionate about his writing. “I am just enjoying it; I have fun. The blank bit of paper; it’s all there for me to put anything I want. You can just let your imagination run riot. It’s total freedom.”

You’re always free, Welsh says, when you’re exercising your imagination.

Welsh sees no need for drugs to boost his creativity. Writing, he says, is a drug in itself. “You don’t need to augment that or enhance it in any way.”

Welsh sees no need for drugs to boost his creativity. Writing, he says, is a drug in itself. “You don’t need to augment that or enhance it in any way.”

At Jaipur, Welsh was in conversation with Chandrahas Choudhury in a session that delighted the audience, not least his fellow Scots.

He was funny, honest, and forthright. Trainspotting, he said, was supposed to be the most shoplifted book in Britain. “Mostly by myself at that time,” he joked.

Welsh has just released Dead Men’s Trousers, the fifth book in the Trainspotting series and his 12th novel to date.

Speaking about going on tour and being given gifts, he remarked that he has spent half his life trying to score drugs and half of it (now that he is touring and frequently crossing borders) trying to avoid them.

His younger self would be horrified to see his older self flushing drugs down the toilet, he said.

Welsh told the audience that he is not materialistic, but into experiential decadence. “I like to live in the moment, to enjoy life in the moment,” he said.

He works on music and writes at the same time, at a standing desk. “I let the subconscious do the heavy lifting,” he said. He has an album coming out in April.

Talking about Big Pharma, Welsh told the audience at Jaipur that health was a “massive scam for late capitalism”, the idea of keeping you alive for as long as possible, but also keeping you sick as long as possible.

Elaborating on this for Changing Times, he said that Big Pharma was one of the world’s last remaining profit centres.

“Most young kids now are never going to be able to work and earn a wage, or earn a substantial wage, so the banks need to get the assets of the parents of these kids and they do that through housing, they do that through health, and they do that through education principally.”

These, Welsh says, are the last vestiges of the current economic paradigm, which is on the verge of collapse.

“Humanity’s in an existential crisis because we don’t know what’s round the corner. We don’t know how we’ll live in a post-capitalist society. We’re heading for a society where there are no wages, no profit, and zero economic growth. How do we cope with that? What do we do?”

People who are resisting the current reality, Welsh says, tend to shut it out.

“We invest in ignorance; we invest in the loudest-mouth idiots who have the populist soundbite.”

Rather than embrace the harshness of the current reality, people are peddling the myth of a golden era in which everybody was relatively prosperous, which didn’t exist, Welsh says.

It is tough for young people today, he says, “because there’s no culture to sustain the bad stuff”. It’s a media culture through the internet now, Welsh says, rather than living local communities and national cultures.

Welsh talks about the “psychic plague” that is marking the transition from capitalism to conceptualism.

“It’s all going on in our heads now; we’re overloaded and we’re trying to make sense of the world as it’s changing around us; we’re doing that through either painkillers or altered states, which are the things that drugs offer.”

It’s ironic, Welsh says, that people on the right who were supposed to be enhancing and defending capitalism and getting back to a market society are the ones who have destroyed it.

It’s ironic, Welsh says, that people on the right who were supposed to be enhancing and defending capitalism and getting back to a market society are the ones who have destroyed it.

“They’re the ones who are almost like the Marxists, and it’s people on the left like myself – the social-democratic left – who are actually trying to preserve the vestiges of capitalism until we can work out what to do.

“It’s weird that the left are the pro-capitalist conservatives in a way; we’re trying to defend this very oppressive economic system, but in the knowledge that it’s the only one we’ve got.”

The political institutions in the West that were set up for an era of industrialisation – an era of imperialism – are now failing, Welsh says.

“Now it’s about what kind of life we want. Do we want a life of freedom that technology offers or do we want an authoritarian regime which controls us because we don’t have the confidence or the savvy or the self-discipline, the self-awareness, to embrace a life of freedom?”

Welsh, who is now sixty, says older people should stop telling the younger generation how to live.

“Somebody my age shouldn’t really be saying anything to young people; just let them do their own thing. We’ve got nothing to offer. We come from a different epoch, a different generation. Our understanding of life is completely different; it’s a whole different society.

“People like myself are children of late industrialisation; we’re living in a world now that we can only understand through interactions with youth, what they choose to tell us and show us about the world.

“The whole of our political and social life is suffering from old people telling young people what to do and holding back the progress of history. I wouldn’t give anybody over forty the vote now.”

Climate change

In the session about climate change, the Australian professor, ecologist, author, and naturalist Darryl Jones, who wrote The Birds at My Table, talked about the “surprising and deeply alarming” changes that have occurred in animal distribution.

In the session about climate change, the Australian professor, ecologist, author, and naturalist Darryl Jones, who wrote The Birds at My Table, talked about the “surprising and deeply alarming” changes that have occurred in animal distribution.

Jones spoke about the dramatic example of salt-water crocodiles who used to be way up in the far north of Australia, but were “slowly but absolutely” coming south and were now appearing in some of the really important tourist spots. “We’re changing the planet fundamentally,” Jones said.

We have deluded ourselves, he said, that we are separate from nature and “we couldn’t be more wrong”.

The author of The History of Bees, Maja Lunde, talked about the probability of there being, in the future, parts of the world, including southern Europe, where it would become impossible to live. “That scares me so much because we will then have refugees on a scale that we have never seen before,” she said.

Mridula Ramesh, who is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, which is focused on waste and water solutions and education, told the Jaipur audience that India was the country most affected by climate change.

Voices of the Young

The session “Voices of the Young” brought together 12-year-old poet and author Anoushka Sabnis, who published her first book, Once Upon a Verse: Because Poems Tell Stories, in 2017 and has been composing stories and poems since she was five years old; 15-year-old Mehul Jangir, who published his first book, Survival: Sandstorm, in 2018 and is currently working on his second; and 17- year-old Ritwij Shandilya, who is the youngest Indian to write a novel in French and also wrote the novel The Rise of Queen Revathi.

This year, the Jaipur festival again spanned generations, genres, cultures, and continents and those who have come to love the bounteous literary feast it offers have already marked the dates for 2020 in their diaries.

Over the five days of the festival Abhishek Singh painted the story of Nachiketa and Yama (death), told in the Katha Upanishad.

Categories: India

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts